El Niño and SUPERCELL (the novel)

Last week I blogged about El Niño and its connection, or lack thereof, to wintry weather in the Deep South. This week I’ll take a look at El Niño and its influence on severe storms–supercells and tornadoes–in the same region.

Last week I blogged about El Niño and its connection, or lack thereof, to wintry weather in the Deep South. This week I’ll take a look at El Niño and its influence on severe storms–supercells and tornadoes–in the same region.

There’s a late-winter/early-spring climatological maximum in Dixie of severe storms (before the focus of the turmoil shifts to the Great Plains), so that’s the season I’ll examine.

Most people will be happy to learn that El Niño-influenced weather patterns have a damping effect on violent storms at that time of year in the South. That is, there are fewer slam-bang thunderboomers around as compared to, say, a La Niña year.

But, there is an exception. Isn’t there always? Over Florida and adjacent areas of Alabama and Georgia, there’s actually an enhanced probability of big rumblers and twisters. That’s because in an El Niño year, the southern branch of the jet stream, a contributor to thunderstorm violence, races over the Gulf of Mexico and the Florida Peninsula.

A couple of cases-in-point: (1) During the “very strong” El Niño of 1982-83, a mid-March ’83 tornado outbreak swept over south Florida. But something even worse followed during the next “very strong” El Niño in 1997-98. (2) The Kissimmee tornado onslaught in late February ’98 turned out the be the deadliest in Florida’s history, claiming 42 lives.

I mentioned earlier that the jet stream is a contributing factor to violent weather. There are many other ingredients that come into play, but the jet is a major component. Thus, I get apprehensive whenever a powerful jet, not content to remain positioned over the Gulf and Sunshine State, is forecast to invade the skies over the interior Southeast, where I live.

That happened in early 1998, after the Kissimmee disaster. In late March, a rash of tornadoes raked the area from Georgia to Virginia killing 14, including 12 near Gainesville, Georgia. In early April, an F-5 twister slammed into a suburb of Birmingham, Alabama, claiming 32 lives (see photo above).

Less than 24 hours after that, an F-2 dipped into the suburbs of Atlanta (about 5 miles from my house, as the falcon flies). Locally, the event is known as the Dunwoody Tornado. Later in April, another tornado outbreak, including an F-5, battered Middle Tennessee.

In summary, while El Niño-touched seasons may bring, on average, a reduction in the number of severe weather threats to the interior Southeast, “very strong” El Niños, such as the one underway now, may harbor some nasty surprises.

I’m not saying the upcoming severe weather season in the Deep South will be any worse than usual. But come the Dogwood blossoms and longer days with their warming embrace, pay attention to the forecasts and be prepared . . . AS YOU ALWAYS SHOULD BE.

Oh, and what about severe storms on the Great Plains, the setting of my thriller SUPERCELL, this spring? There–good news for most people, bad news for chasers–El Niño-impacted weather patterns often bring a reduction in the number of twisters.

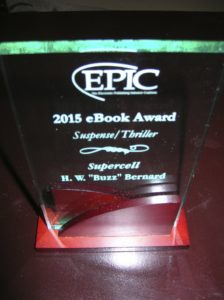

So chasers, if you think you might experience withdrawal symptoms, may I be so bold as to suggest a particular novel?